The Longhouse

Here follows the first in a series of House Type Typologies.

The rural longhouse was a natural and necessary evolution of the byre-dwelling where people and animals lived in one room. The traditional Byre-House, common in the Irish rural landscape were dwelling houses generally constructed in three distinct sections to accommodate livestock as well as people. People lived at one end and the animals lived at the other all under the one roof. Over time these dwellings were modified & adapted to suit developments in agrarian practice ultimately leading to the development of the Longhouse.

The Irish Cottage

The Irish cottage had a distinct and recognisable style. Notably by using local materials, it blended seamlessly into the landscape. Built of stone, clay, sods, grass and straw, simple materials brought from the vicinity, the house harmonised with the landscape to which it belongs.

The roof was mostly thatched, reflecting locally available materials and ensuring the rain runs off. The hearth in the centre of the home, the centre of cooking, warmth, and water-heating, but also the social centre where stories were told, songs sung, and life shared.

How many of us spent many a wistful hour by the fireside with elderly relatives unaware that the simple functional form of dwelling had its origins firmly rooted by the practical sophistication of their forefathers & thus, the same can be said of the pedigree of the modern iteration of the longhouse. The essence of architecture responding to the needs of its inhabitants.

Threading the lineage of the Modern Longhouse from its humble beginnings it becomes apparent that a number of features remain common: the Irish vernacular cottage is rectangular, divided into rooms which occupy the full width of the house with no central hallway or passage; it has thick strong walls, a steeply sloped roof supported by the walls rather than pillars or posts; there is an open hearth at floor level, with a chimney protruding through the roof ridge; they are usually one storey high, and have windows and doors in the sides of the house.

From the end of the 19th century it became common for longhouses to be coated in layers of limewash (see top picture), although more remote buildings were normally left untreated. Limewash rendered longhouses with thatches have become a quaint, fundamental ingredient of popular Irish culture.

In Scotland

A Blackhouse or tigh-dubh is a traditional type of Longhouse which used to be common in the Scottish Highlands, the Hebrides, and indeed Ireland.

The buildings were generally built with double wall dry-stone walls packed with earth, and were roofed with wooden rafters covered with a thatch of turf with cereal straw or reed. The floor was generally flagstones or packed earth and there was a central hearth for the fire.

In this example it is notable that there was no chimney for the smoke to escape through. Instead the smoke made its way through the roof. This led to the soot blackening of the interior which may also have contributed to the adoption of name Blackhouse.

The Irish Longhouse

These modest buildings or vernacular houses, remind us of a time when daily life had few of the conveniences, we take for granted today. Their existence demonstrates the considerable resourcefulness and skills of the ordinary men and women who often worked mainly with the raw materials around them. People at the time made good use of local readily available materials, stones, slates, crops, grasses, reeds, mud, sod and turf as they built and maintained the distinctive houses that are widely regarded as an integral part of the Irish rural landscape.

One of the strongest characteristic of this typology is how well the structure is sited within the landscape and how the primary dwelling, ancillary buildings and the landscape interrelate with each other.

The Longhouse, as a development of the Byre-House are generally single-storey structures which typically had a kitchen with fireplace in the centre with a bedroom at one or both ends. The main bedroom was usually adjacent to the kitchen and had its own hearth. They tended to be longer than they were broad mainly because trees were scarce and builders had to use fossilised wood found in local bogs. Over time, when the size of accommodation needed to be increased in size this could generally be done in a variety of ways. In many cases it was common to add a bedroom at one or both ends of the original house. If there was already an outbuilding at the end of the house, then this was sometimes converted into a bedroom. While these buildings typically became longer than their predecessors, the width of the buildings remained unchanged.

The Longhouse Variation: The Dog -Trot

The ‘Dog-trot’ is described as a roofed passage similar to a breezeway; especially: one connecting two parts of a cabin. The dogtrot variation on the Longhouse also known as a Breezeway House, is a style of house that was common throughout the South-eastern United States during the 19th and early 20th centuries.

A Dog-Trot house historically consisted of two equally proportioned log cabins connected by a breezeway or “dogtrot”, all under a common roof. Typically, one cabin was used for cooking and dining, while the other was used as a private living space, such as a bedroom. The primary characteristics of a dogtrot house is that it is typically one story, has at least two rooms averaging between 18 and 20 feet (5.5 and 6.1 m) wide that each flank and an open-ended central hall, the Dog-Trot. The main style point was a large breezeway through the centre of the house to cool occupants in the hot southern climate.

Origins

While it’s hard to pin down the exact origin or antecedent of this building typology in the United States, there’s much evidence that earliest forms of dogtrots came into existence here in the lower Delaware Valley colony of New Sweden in what we now know as New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Delaware. It is believed that Swedish and Finnish settlers of North America in the mid-1600s brought a building typology known as the ‘pair-cottage’, from Northern Europe. These pair-cottages consisted of a pair of log cabins stationed side-by-side and joined with a common grass-covered roof. The Fenno-Swedish settlers were accustomed to working with large timbers and hewing logs for construction and as early settlers of the lower Delaware Valley it made sense that their woodworking skills were put to use in constructing their early homes.

The origin of the early dogtrot’s construction methods as linked log cabins is telling as well. There were two major limiting factors in the construction of log cabins – the first was the length of log that a team of men and livestock could handle. The second was the availability of such raw materials. Selecting logs of a length able to easily be moved into place, especially above one’s head, limited the size logs one could use to build the log structure with and thus the length of the walls. Equally, a log’s taper was a critical factor as the taller log sections yielded more taper. Accounting for these factors during construction ensured the log cabins remained small and one-story.

Once a log structure was completed, adding to it presented difficulty. In timber fame & traditional masonry construction of the present day, additions are accomplished simply without much thought and in virtually any location. Lacking any way to modify the supporting walls of the log structures meant the only means of adding to the structure was to build yet another neighbouring structure – again subject to all of the previously noted limitations. Building the second cabin only a few feet away would’ve resulted in a useless and dark intervening space. But by separating it a rooms’ width (12 – 16 feet) away it doubled as an additional outdoor, multipurpose room. All of this was accomplished with a simple, singular gesture.

The Frontier Cabins

The dog-run, dog-trot, or double log cabin was a common type of house in Texas at the middle of the nineteenth century. The building consisted of two cabins separated by a ten or fifteen foot passageway, with a continuous gabled roof covering both cabins and the passageway between them. Often a porch or veranda was built to extend across the entire front of the house, and lean-to shed rooms were constructed at the rear of each cabin for additional space. The walls were made of horizontally laid hand-hewn logs, with the openings between the logs chinked with sticks and clay. Later examples were often frame rather than logs. The floors were of either dirt, sawn boards, or split logs with the flat side up. There were few windows in frontier cabins, and glass windows were rarely seen in pioneer times. Each cabin had a door opening onto the dog-run. Doors and shutters were hung on rawhide or wooden hinges. The roofs were made of overlapping oak clapboards held in place by weight poles. The chimney was constructed of sticks and a clay mixture, and the hearth was made of smooth rocks. Later dog-run houses often had fine brick chimneys and shingled roofs. The purpose of the dog-run was to cool the house by providing shade and catching the breeze. The space served as a catch-all for farm and household articles and was the favourite sleeping place of the dogs. The structure was used on the frontier from Alabama to Ontario and has European ntecedents.

Layout

The dogtrot plan layout is characterized by two equal rectangular shaped, single-story rooms termed ‘pens’; separated by a common, usually gabled, roof and a floored breezeway or dogtrot which spans the full depth of the plan. Each of the pens was accessed via a door opening onto the dogtrot separating the structures. The dogtrot behaved as an additional room. The functions of each of the flanking pens were usually different. One was used as private living space and the other as a kitchen and dining or any number of secondary uses: workshop, office, apartment, storage, tavern, or inn.

The intervening space, the dogtrot, served many purposes. Access between either pen and the dogtrot was simple and direct. Some historical examples omitted the floor in the dogtrot breezeway leaving bare earth. This created a covered place to service wagons – a sort of modern day carport or provided ready access to a sheltered farmstead courtyard. The more common configuration placed the floor coplanar with the interior space. In this way it functioned more like an additional outdoor room – a porch, a place to store farm implements and a place to sit out of the sun. This ensured a social status to the dogtrot as the central gathering point in these early homes.

The dogtrot design is known well in southern building cultures of the United States. It permeated southern pioneer architecture in part because it had offered an ingenious solution to the region’s hot climate. The dogtrot’s breezeway, positioned centrally in the plan, naturally created a cooler pool of air between the warmer interior spaces. This cool pocket of air could easily be drawn into the flanking pens by opening the doors at either end of the gables. In a time before air conditioning, one can see the draw of this passive cooling effect.

Chimneys

Providing heat to the enclosed ‘pens’, one chimney could be found on the gable ends of each structure. Early incarnations were constructed of wood, but proved extremely dangerous. Later versions were more fire-resistant and permanent built of brick and stone.

Porches/Verandahs

Many dogtrots included a veranda along an entire eave wall. The porch or veranda usually had a shed roof with a lower pitch than the main roof and over time the exterior spaces of these porches were enclosed and apportioned to interior use.

Windows

Symmetrical window configurations were most common, with one or two windows per pen on each eave wall and two windows flanking the chimneys on the gable ends.

Attics

In keeping with the efficient use of space, full adoption of the attic space for both storage and even extra living space was common. This expanded the use of an often extremely compact building footprint.

Additions

The historical record indicates that dogtrots were of two origins. Those that began with one structure added a second and connected the two with the roofed dogtrot. And, those that began by constructing and connecting both pens at once.

Other additions took to enclosing verandas, making each pen two rooms deep leaving essentially a foursquare plan, and even separated structures. The separate structure was popular in the south, where the kitchen would be housed in this separate building connected by a covered breezeway. This removed the largest source of heat from the living space and limited losses in the frequently devastating fires.

Materials

Log construction formed the basis for early dogtrots; the joint imperfections were filled with clay and twig chinking to keep out the elements. The interiors of these log structures used clapboards and board and batten wood finishes to conceal the roughly hewn logs. The limitations of log length and taper, had a substantial impact on the scale of early dogtrots. Equally, the raw materials available locally meant most of the structures utilized the wood from the surrounding forest – notably pine and spruce.

With advent of large scale lumber mills and the mass-produced wire nail in the late 1800’s the raw materials and methods of home construction transitioned away from log construction toward light frame construction which persists today as the most popular form of construction. Stick-frame construction being modular and infinitely flexible changed the construction requirements of additions and renovations. Sticks could easily create additions and loads could be transferred to the foundation by simply joining them together to create headers. Holes could be cut in walls and extensions weren’t limited to the size of logs.

The Modern Longhouse

The Modern longhouse is a dwelling typology which is eminently adaptable to many site variants, whether flat or with a challenging contour profile. The traditional Byre- Houses & Longhouses were derived as response to the availability of materials, limitations on the availability of manual labour & the typography of the site & today, the Modern Longhouse typology, being essentially a simple form of construction, can also take advantage of the same genetic factors; standardised & manually manageable material, sensible structural detailing, ability to embrace local materials. It’s a versatile and economical plan to construct. A simple and affordable way to unite a family under one roof.

At only 6m wide (20 feet) wide a is short enough for the entire footprint to be efficiently spanned by simple pitched roof comprising relatively inexpensive prefabricated trusses.

Using this form of construction, volumetric drama can be brought to bear on the internal spaces by the utilisation of vaulted prefabricated roof trusses. Vaulted ceilings to Living & Bedroom spaces & flat ceilings to the Kitchen/Dining area, secondary utility spaces, bathrooms & transition spaces with the living spaces providing further opportunities for the provision of accommodation within the loft spaces.

The very lack of any strict functionality makes it inordinately useful and adaptable.

The Modern Dog-Trot Longhouse

With the necessity for additions no longer hindered by the dimensions and heft of the log, and social pressure to promote one’s status via their home, the dogtrot succumbed to other more stately building types. Today those in the south who grew up knowing the typology often recall the dogtrot fondly, but at the time it was considered to be a very humble shelter. Which is to say, built for the poor. As such these homes didn’t correlate well with wealthy plantation owners and with time it gave way to grander and more sprawling architectural styles.

As an architect interested in humble structures, I find the Longhouse, and its Dog-Trot derivative to be particularly compelling – in its climactic response, its simplicity, its affordability and fort its flexible integrated indoor/outdoor space. I think this is why the Modern Longhouse & the Dog-trot, remains a viable and sought after plan for many today.

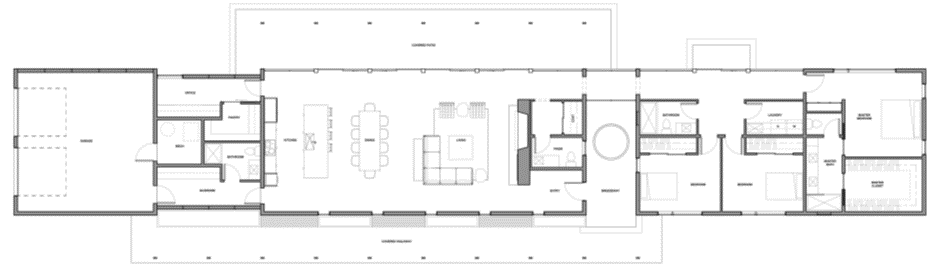

Modern Longhouse Dog-Trot Floorplan

While the Irish climate isn’t subject to the same stifling heat as the deep south of the United States, our winters and shoulder seasons beg for flexible transition zones between indoors and out. The dogtrot layout is the perfect corollary and it addresses this need elegantly. Think of it as an expanded mudroom, a place to store kayaks paddles and kick off your mud boots under cover of weather. Pair it with a set of sliding screens and it’s a screened porch, a winter garden a garden room, or could just be left open as a true breezeway but sheltered with a roof over it, a kind of outdoor living room.

Add a fireplace and it’s a sheltered outdoor dining area. Add benches and it’s a living room or sleeping porch, or play space. All kinds of opportunities arise here within a really simple shape.

Contributions from the following authors of source material for this article is gratefully acknowledged:

Laura Bowen Architect: lbowenarchitect@gmail.com

Kildare County Council/ heritage publication Re-using Traditional farm buildings

Christiaan Corlett: http://www.christiaancorlett.com/

Wicklow’s Traditional Farmhouses.

Eric Reinholdt 30X40 Design Workshop: https://thirtybyforty.com/

Hebridean Homes: https://www.hebrideanhomes.com/

Lunchbox Architects: https://www.lunchboxarchitect.com/featured/trentham-long-house/

https://theimageplane.wordpress.com/irish-longhouses/

Samuel Watson, samrocconi@hotmail.com